Synopsis

Jennifer Brea is a Harvard PhD student soon to be engaged to the love of her life when she’s struck down by a mysterious fever that leaves her bedridden. She becomes progressively more ill, eventually losing the ability even to sit in a wheelchair, but doctors tell her it’s "all in her

head." Unable to convey the seriousness and depth of her symptoms to her doctor, Jennifer use the internet, Skype and Facebook to connect to each other—and to offer support and understanding.

Director

-

Jennifer BreaUnrest (2017)

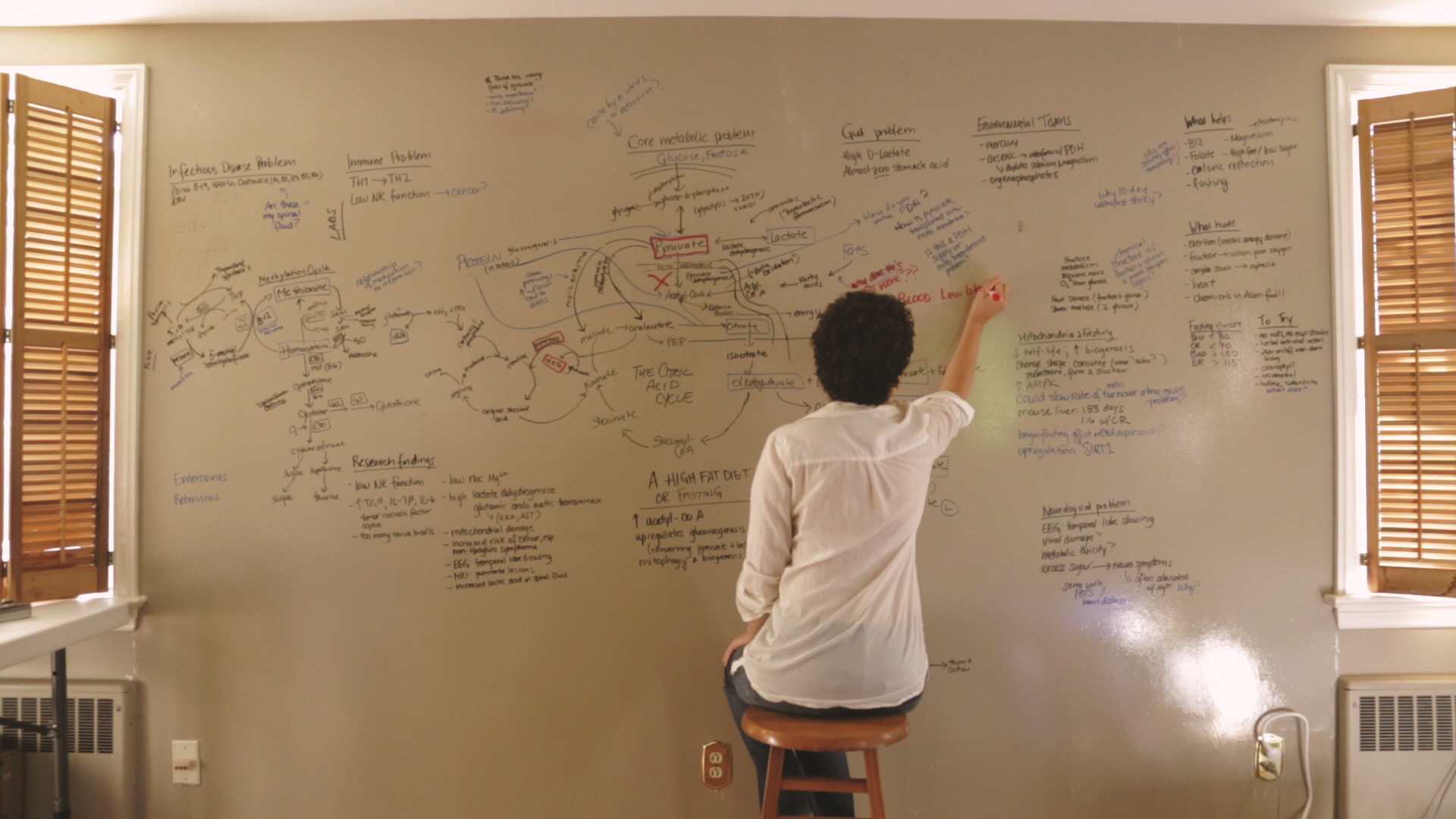

Jennifer BreaUnrest (2017)nrest is a personal documentary. When I was 28, I became ill after a high fever and, eventually, bedridden. At first, doctors couldn’t diagnose me and later began telling me that either there was nothing wrong with me or that it was in my head. As I began searching for answers, I fell down this rabbit hole and discovered a hidden world of thousands of patients all around the globe, many of whom are homebound or bedridden and use the internet to connect

with each other and the outside world.We were all grappling with a disease called ME, more commonly known as as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. This wasn’t a disease I had ever really heard of, read about, or seen films made about, even though it is an extremely common condition. It’s a story that’s been flying under the radar for the last 30 years.

Unrest follows the story of me and my husband Omar. We are at the very beginning of our marriage, of our lives together, when this asteroid hits. And at the same time, I start reaching out to other patients and documenting their stories. We meet Jessica, for example, a young girl in England who has been bedridden since she was 14, and Ron Davis, a Stanford geneticist who is trying to save his son’s life in spite of some incredible obstacles.

I made this film four times. At first, it was just an iPhone video diary. Those first few years, I could barely read or write but needed an outlet. And so I started creating these really intimate, raw videos.

Then I went online and met thousands of people, all over the world, living the same experience. Many were homebound or bedbound, isolated, without treatment or care, and often disbelieved. I thought, “How could this have possibly happened to so many people?” There was this deep social justice issue at the heart of it. An entire community had been ignored by medicine and had missed out on the last 30 years of science. A part of the problem is that many of us are

literally too ill to leave our homes and so doctors and the broader public rarely see us. That is when I decided to make a film.When we began shooting, I was completely bedridden, so I built a global producing team, hired crews around the world, and directed from my bed. I conducted interviews by Skype and an iPad teleprompter—a sort of poor man’s Interrotron. We had a live feed that (when it worked!) allowed me to see in real time what our DP was shooting on the ground. Filmmaking allowed me to travel again.

As we started shooting, and I started to get to know these amazing characters, the film became about some of those burning questions that I had. What kind of a wife can I be to my husband if I can’t give him what I want to give? How do I find a path in life now that the plan I had has become impossible? If I am never able to leave my bed, what value does my life have? And I started to become interested in what happens not only to patients but to our caregivers when we

3 or a loved one are grappling with a life-changing illness. These are questions we will all face at some point in our lives.Lastly, there was a point at the middle of the edit when we had a very strong cut but I felt unsatisfied with just seeing us, these bodies, from the outside. I knew that there was so much about this experience that an external camera just couldn’t capture. And so we started bringing in these elements of personal narration, visuals, and sound design in an almost novelistic way, to try to give the audience glimpses of our dreams, our memories. It was important to me to convey that regardless of our profound disabilities, we are all still fully human. That even laying in bed, we have these complex, inner lives.

It’s my hope that in sharing this world and these people that I have come to profoundly love, that we can build a movement to transform the lives of patients with ME; accelerate the search for a cure; and bring a greater level of compassion, awareness, and empathy to millions upon millions of patients and their loved ones wrestling chronic illness or invisible disabilities.

Review

Chronic fatigue syndrome is an invisible disease. The patients are often misunderstood as having mental issues or illnesses as it is hard to convey their sense of weakness, powerlessness, and dreadful fatigue. Patients diagnosed of this syndrome feel relieved and even happy at times because they have been confirmed as sane, and because they now have a name for their pain. Jennifer Brea, the director, explains the reason why she filmed herself crawling on the floor: “I thought someone had to see this.” Though things may not have been clear the first time she pressed the camera button on her iphone, she must always have known. That is a matter of survival at stake, for her to make this illness visible. Just like those people who tried to prove the existence of ghosts by placing cameras in all corners of rooms, she films this to prove that her disease and herself undergoing this disease, exists. The camera eventually becomes an instrument connecting patients. Those who were swallowing their pain in solitude meet through Youtube and Skype to become a community.

Living with a disease is not only about struggling with the causes or symptoms of that illness. It also means protesting against the wrongful stories the society imposed upon that disease. This film, a record of the effort to visualize an illness, by a director who is going through this powerless state of ailment, allows us to 'see' that making one’s own story and making one be heard can be a way of enabling life. [May]

Credits

- Director Jennifer Brea

- Producer Jennifer Brea, Lindsey Dryden, Patricia E. Gillespie, Alysa Nahmias

- Editor Kim Roberts, Emiliano Battista

Contribution & World Sales

- Contribution & World Sales THE FILM COLLABORATIVE

- Phone 1 323 2078321

- E-mail jeffrey@thefilmcollaborative.org